Green Hydrogen Production Boosted by Defect-Engineered Catalysts at UNICAMP

February 10, 2026If you’ve been following the global push to decarbonize heavy industry and transport, you know green hydrogen production is the shiny new star in the renewable energy lineup. The snag? Those platinum-based electrolysis catalysts can cost a fortune. Enter research whizzes at State University of Campinas—better known as UNICAMP—in São Paulo. With a little help from FAPESP, they’ve whipped up a fresh batch of defect-engineered catalysts that offer the same—or even better—performance at a fraction of the cost. By strategically introducing tiny flaws into cheaper materials, they cranked up hydrogen output by 32% just by dialing defects up by 30%. Suddenly, affordable green hydrogen looks less like a pipe dream and more like Brazil hydrogen research reality.

It’s no coincidence that this breakthrough hails from São Paulo state, Brazil’s powerhouse when it comes to industry, hydropower and biofuel know-how. Since opening its doors in 1966, UNICAMP has evolved from a local science hub into a heavyweight in materials science, energy storage and hydrogen tech. These days, its labs are a hotbed of earth-abundant material experiments, building on decades of work—starting with platinum-iridium electrodes in the 1970s and moving through molybdenum disulfide and nickel-based alloys in the 2010s.

How tiny defects fuel a big jump in hydrogen output

Turning flaws into features for better catalysts

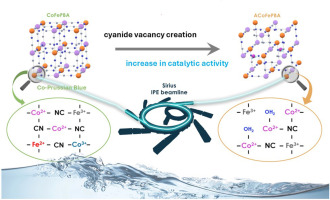

At the core of this innovation is defect-engineering—basically carving out or shuffling atoms in a catalyst’s crystal lattice to create more active spots. Back in the 1970s, researchers leaned on platinum-iridium alloys for the oxygen evolution reaction, but scarcity forced labs to hunt for alternatives by the 2010s. That’s where materials like MoS₂ and nickel-iron layered hydroxides came into play. The UNICAMP crew took the concept further: using controlled etching and heat treatments, they dialed in defect density like a volume knob. Electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction confirmed the lattice was precisely warped. The payoff? Faster charge transfer, lower overpotentials by tens of millivolts, and—get this—32% more hydrogen with just 30% more defects.

What’s even cooler is you don’t need a sci-fi fabrication line to pull this off. Simple chemical tweaks—playing with etching time, temperature, that sort of thing—can fine-tune those flaws. After a few rounds of cyclic voltammetry and gas chromatography, you end up with a catalyst that can go toe-to-toe with pricier platinum-group metals. For anyone eyeing industrial-scale green hydrogen production, that’s a big deal.

Who’s behind Brazil’s catalyst comeback

This project springs from a multidisciplinary team at UNICAMP, a public research university that’s been at the forefront of renewable energy and materials science since the ’60s. Nestled in São Paulo state—with its abundance of hydropower and biofuel resources—the university provides the perfect breeding ground for innovation. A big shout-out goes to FAPESP, the São Paulo Research Foundation, which kicked in dedicated funding for green hydrogen initiatives.

The researchers say they benefit from an ecosystem that encourages collaboration—chemists, materials scientists and engineers all huddled around electrochemical workstations hooked to real-time monitoring systems. These setups let them tweak defect densities and benchmark performance on the fly. While the individual whizzes behind the scenes might not be household names, the group’s partnerships with industrial players mean these catalysts could soon get tested under real-world plant conditions—a key step from bench to factory floor.

This isn’t happening in a vacuum. It builds on a decade of global trends, moving from lab-scale MoS₂ tweaks and nickel alloys to this new breed of defect-engineered catalysts. It puts Brazil hydrogen research on the same map as European and North American pioneers experimenting with strain-engineered alloys and phase-transition methods.

The ripple effect for renewables and the economy

Lower-cost catalysts can spark a chain reaction throughout the green hydrogen production value chain. Swap out platinum-group metals for these defect-rich alternatives, and electrolyzer production costs could plummet by up to 90%, according to the UNICAMP and FAPESP findings. That kind of savings could fast-track adoption in tough-to-decarbonize sectors—think steelmaking, chemical plants and long-haul transport.

For Brazil—home to one of the world’s largest hydropower networks and a booming biofuel industry—this breakthrough slots right into a bigger clean energy playbook. Local manufacturing of affordable catalysts cuts down on imports, bolsters the supply chain and creates high-tech jobs in São Paulo state. Around the globe, investors and policymakers are eyeing these developments: the green hydrogen market is forecast to skyrocket more than 100-fold by 2030, so adding Brazil to the innovation roster matters.

Worldwide, labs in Europe are tweaking MoS₂ to rival platinum, while U.S. researchers test strain-engineered nickel-iron alloys. But few can match the sweet spot of low cost, simple synthesis and solid performance gains. By showing industrial-scale cost parity with noble-metal catalysts, UNICAMP could tip the balance in favor of mass adoption. Of course, lab success is one thing, industrial longevity is another—issues like catalyst degradation, sintering and fouling still need stress tests over thousands of hours.

Roadmap to scaling up

Thanks to a multi-year grant from FAPESP, the team’s plans include scaling their recipe from milligram batches to gram-level quantities—a must before any pilot plant run. They’re also looking to slot these defect-engineered materials into membrane-electrode assemblies, the beating heart of commercial electrolyzers. If it all checks out, manufacturers could swap their current inks for these new slurries, slashing both material and processing costs.

Several Brazilian energy firms have already raised their hands to test these catalysts in on-site electrolysis units powered by hydropower reservoirs. These pilot projects won’t just measure performance—they’ll push long-term stability and how well the catalysts handle fluctuating power from wind and solar farms.

Looking ahead, UNICAMP aims to team up with electrolyzer manufacturers for pilot tests and stress trials. The focus: durability, cycling performance and seamless integration with variable renewables like wind and solar.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s government and energy agencies are rolling out green hydrogen roadmaps, eager to weave domestic innovation into national decarbonization strategies. In that light, defect-engineering could become a cornerstone technology—one that labs worldwide refine with hybrid materials or smart coatings down the line.

At the end of the day, it’s a neat reminder that sometimes the tiniest imperfections spark the biggest breakthroughs. By embracing defects, these researchers have opened up new avenues for affordable, scalable hydrogen. And for anyone watching the clean energy shift, it’s clear that progress often happens in the smallest of steps—one nanometer at a time.

source: sciencedirect.com

With over 15 years of reporting hydrogen news, we are your premier source for the latest updates and insights in hydrogen and renewable energy.

With over 15 years of reporting hydrogen news, we are your premier source for the latest updates and insights in hydrogen and renewable energy.